Derniers Produits

-

Promo !

Echarpe unie Scarf Marine | Écharpes et Foulards Saint James Femme

€ 106.47€ 60.06 Ajouter au panier -

Promo !

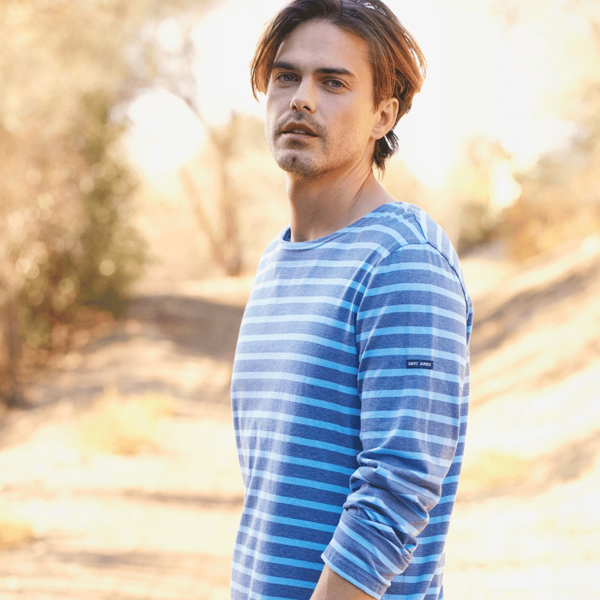

Pull marin Bretagne Marine/Persan | Pulls Marins Saint James Homme

€ 125.22€ 79.17 Choix des options -

Promo !

Marinière col bateau Guildo Marine/Ecru | Marinières Saint James Homme

€ 130.13€ 60.06 Choix des options -

Promo !

Marinière Minquiers Smiley Neige/Marine | Marinières Saint James Homme

€ 106.47€ 60.06 Choix des options

Produits Présentés

-

Promo !

Polo manches 3/4 Oléron Emeraude | Polos & T-shirts Saint James Femme

€ 136.05€ 60.06 Choix des options -

Promo !

Porte-monnaie Aventure Marine | Petite maroquinerie Saint James Femme

€ 100.56€ 60.06 Ajouter au panier -

Promo !

Pull col rond Rumilly Austral/Insigne | Pulls, cardigans, vestes Saint James Femme

€ 168.17€ 77.35 Choix des options -

Promo !

Chemise à carreaux Gavin Ecume/Emeraude | Chemises Saint James Homme

€ 94.64€ 60.06 Choix des options